This is a revised and updated post which was originally published on June 2, 2010.

History

Although not as significant in the US as in the UK, hedgerows nonetheless offer a valuable design opportunity for wildlife habitat. In the simplest terms, a hedgerow is a row of wild trees and shrubs, packed closely together. In the UK they have a very long and interesting history, dating back thousands of years. They were a mixed blessing, good for wildlife, but very bad for peasant farmers. Historically, hedgerows were the remnants of woodlands cleared to make way for agricultural fields. With the passing of the Enclosure Acts of the 18th and 19th centuries, hedgerows were created in great numbers throughout much of the UK as a fencing boundary. Prior to this farming was done in open, common fields. The result of the Enclosure Acts was that peasant farmers, or those who failed to prove ownership, despite generations of farming their land, were driven out of the countryside and into the cities where they turned to the factories and witnessed the start of the industrial revolution. Hedgerows were so pervasive in the British countryside that they were frequently mentioned in texts using such words as haeg, gehaeg, haga and hege which are to this day still found in place-names around the country.

However, hedgerows date even further back, to ancient civilizations who used them to delineate areas as they were less expensive, and more permanent than fences. The Romans used them as field boundaries with Julius Caesar describing them in the land of the Belgae during the Roman war with the Gauls. Hedgerows were formidable boundaries and did more than mark agricultural borders, by creating defenses against the Romans, intentionally or not. They had succeeded in making hedges that were almost like walls, by cutting into saplings, bending them over, and intertwining thorns and brambles among the dense side branches that grew out. These hedges provided such protection that it was impossible to see through them, let alone penetrate them. In the end their towns were their weakness which caused their downfall. Perhaps they should have planted hedgerows around the towns as well.

Today, the remaining hedgerows are targeted for protection in the UK. They have become so embedded in the British landscape and so many species of wildlife depend upon them for movement, food and shelter that despite being a human created feature, the ‘important’ ones are now protected from removal.

In the US they have a much shorter history having only been encouraged since the 1930’s by the USDA’s Shelterbelt program. Also called windbreaks, they were planted to aid agricultural fields in the prairies. Used for agriculture they helped prevent soil erosion, decreased livestock stress, increased production and in some states, reduced snow drift. However, many of those windbreaks have been removed because farmers want more tillable acres (PDF). Fortunately, among some sustainable farmers, they appears to be catching on.

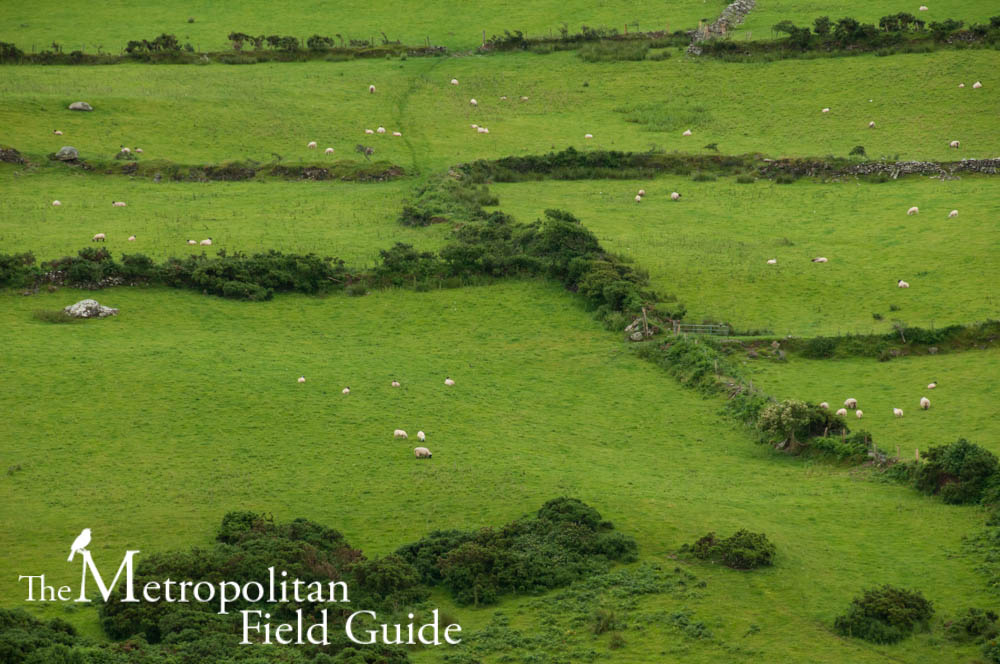

The Irish Hedgerow

The Benefits of the Hedgerow

Hedgerows act in much the same way a woodland or forest edge does. They have good structural diversity, from groundcovers up to trees which provide a multitude of habitat elements. Hedgerows delineate borders, they’re much more aesthetic and less expensive than fences. They also help prevent erosion and soil loss by acting as a barrier and providing soil stability. At the same time they help to prevent flooding by acting as a barrier and the plants intercept rainwater while their roots store water. In this same way they help reduce the amount of pollution. They block or reduce wind which helps surrounding plants from losing water. Hedgerows also provide shade. Indirectly they reduce the amount of pests such as insects and rodents by providing habitat for predators.

Wildlife benefit enormously from hedgerows as they provide an ideal movement corridor for wildlife, connecting small woodland patches or other habitats such as ponds. Many species use it as a travel corridor including bats which use linear edges as commuting routes. They also provide insect habitat, on which the bats can forage. Many butterflies and moths visit hedgerows for foraging as well as a travel corridor and established trees provide a wind shelter. Older hedgerows are rich in decaying wood which provides habitat for beetles. Larger hedgerows are beneficial for birds looking for space to nest and forage. Visit the Hedgelink website for a long list of the wildlife which benefits from having access to hedgerows.

Urban Use

Although they were traditionally used in the rural setting, they have principles that can easily be used in an urban setting. Hedgerows are low-cost while at the same time being a high-impact design element. They can be used along many existing linear landscapes such as railways, pathways, power lines and roads where they can be used to create habitat corridors, connecting networks of habitat patches together. Homeowners can use them to surround their yard, providing all the benefits for wildlife while also providing privacy and creating a very nice space. Homeowners can work together to link stretches of yards creating a travel corridor for small mammals, birds, reptiles and amphibians and insects such as pollinators. They also have the potential to be installed in industrial and commercial areas and to connect patches of habitat.

Hedgerows can also be a habitat concept that don’t quite fit the traditional use of hedgerows. The Urban Hedgerow Project aims to makes space for the feelings and thoughts that urban wild animals and plants provoke. Instead of a row of trees, we are exploring wall-mounted vertical forms that will comprise varied substrates, from repurposed industrial components like plastic tubing and lumber discards, to habitat for indigenous plants”hosts to indigenous fauna. This idea is inspirational and challenges us all to examine existing habitat concepts and then to rethink them to see how they can be applied in more urban settings.

Designing a Hedgerow

The key to a successful hedgerow is diversity, diversity diversity. The diversity of plants and structure ensures the hedgerow can appeal to a wide variety of wildlife by having a diversity of fruiting and flowering times. Having structural layers is important for many reasons; different species inhabit specific vegetation layers, more layers provide more refuge and more sources of food. Leaving dead material on the ground is also important because many species of wildlife forage in the leaf litter for insects and even nest and pupate there. There are a number of plant species that can be beneficial, trees will provide nesting, shelter and food for birds, and shelter for bats, moths and squirrels. Over the long term the trees will die, turning into snags, and provide another range of benefits.

Select shrubs and trees that provide fruit or nuts for wildlife and shrubs with thorns or spines to provide good shelter for many species. Choose shrubs which are known to be the larval host of butterflies and moths. Include a range of plants that flower during various times of the year to provide a constant source of nectar and pollen. If you’re in the Pacific Northwest there is a good plant list from the King Conservation District and another plant list from the Canadian Wildlife Federation. Some of the best choices for Pacific Northwest hedgerows include Pacific Serviceberry,Snowberry, Oregon-grape, Douglas Fir, hawthorn, wild rose, bramble, hazel, beech, dogwood, apple, elm, oak, honeysuckle and clematis. Many of these will be found growing naturally along forest edges or in thickets.

Further Reading:

- Hedgelink: Working together for the UK’s hedgerows

- Hedgerows – Farm to City: King Conservation District

- A Guide to Multifunctional Hedgerows of Western Oregon (PDF):: Oregon State University Extension Service

- Hedgerows offer variety and shelter to urban gardens:: Seattle Times

- Farm Hedges: RSPB

- Ancient and Species-rich Hedgerows: Buglife

- Hedgerows: Canadian Wildlife Federation

- Hedgerows: Their History and Wildlife: Book

4 Comments