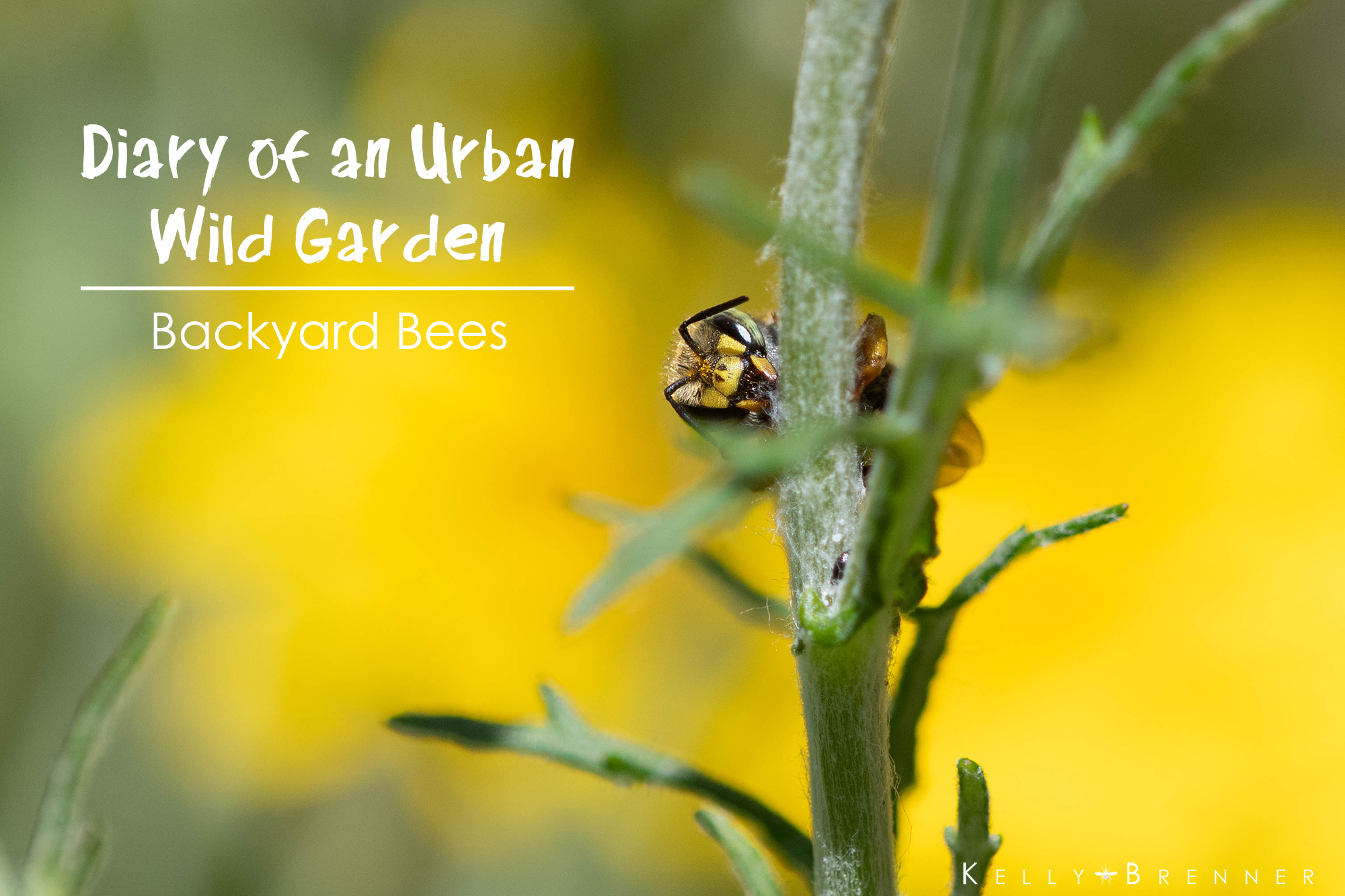

Some visitors come and go and you only catch snippets of their lives, while others hang around and you get to catch the full drama. This spring my small carpenter bees visitors have been the latter. Almost a month ago I watched tiny bees with shiny black bodies resting on broken stems of last year’s aster plants in my wildlife garden. They didn’t go in, they simply sat on the top. I took a few photos and moved on to watching other bees. Fast forward about three weeks and as I wandered around my wildlife garden watching insects, I noticed a small bee on the leaf of my new mock orange plant by the pond. I looked closer, and closer, until I saw it was on top of another bee. Despite my close proximity, the bees didn’t budge at all and I realized as I looked at these two tiny bees, that they were mating. The male was much smaller than the female and had a white patch on his face. I posted the photos to Twitter and learned they were small carpenter bees, Ceratina sp.

Their name, Ceratina, is Greek and means ‘horn’ referring to their antennae. Although there are over 350 species in the world, in North America there are only 22.

Yay!! These are Ceratina sp. (I could maybe id them from the photo)

— TK (@therainbowbee) April 26, 2019

Believe it or not but these lil ones are related to the big chunky carpenter bees! But instead of drilling holes in wood they nest in grass/veg stems. It’s ungodly cute to see them go into a hollow grass blade.

Another week later and I was out watching bees once more on a sunny afternoon. Movement around the same aster stems caught my eye and I saw tiny bees once more on them, but this time they were going inside the hollow stems. I squatted down and watched and almost immediately two came tumbling out of one stem as though fighting. They were so small that I couldn’t quite tell what was going on until I looked at my photos on the computer. It was not two females tussling over nesting space as I first suspected, but a male trying to mate with an unwilling female.

I went back outside to watch now that I had a better idea of what was going on and saw that multiple stems were plugged with a female bee’s back end and the males were flying from stem to stem. The particularly tenacious males would bite the female on her bum and attempt to physically drag her backwards out of the stem. I did not see them succeed in this, but it wasn’t for a lack of trying.

All Ceratina species nest like this, in broken stems or twigs. According to the book, The Bees in Your Backyard, some of the most common plant species for nesting Ceratina are raspberry, rose, sumac, sagebrush, elderberry and buckwheat, among others. Inside these stems, the female lays an egg, leaves a bit of pollen and seals a chamber. Then repeats the process the length of the stem. According to the same book, the females aren’t going anywhere! They guard their nest and eggs until they have fully developed, which can take up to a full year.

Although the species in Seattle don’t do this, some Ceratina species can do something completely unique – reproduce by parthenogenesis. Just like aphids, females of some Ceratina species can produce male and female offspring without having to mate. All female bees can reproduce male bees without mating, but these few Ceratina species are the only that can also produce females.

One of my biggest pieces of advice that I give people who want to make their yard wildlife friendly, is to not tidy too much. These bees are a perfect example why. Had I cut down the old aster stems and tossed them in the compost, I never would have watched this drama play out in my backyard, nor would the bees have found nests here. If you need to cut down the stems of woody plants, place them together in a corner, out of the way somewhere in your yard so they can be used by these solitary bees.

Male Small Carpenter Bee

Female

Small Carpenter Bee

Male Small Carpenter Bee

Male

Small Carpenter Bee Dragging out Female

Male

Small Carpenter Bee Dragging out Female

Mating Small Carpenter Bees

Thank you for sharing.