On Being Misunderstood is a new feature at The Metropolitan Field Guide which will look at the variety of flora and fauna we live with which are too commonly misunderstood. From plants to wildlife, many of our daily interactions with these species are often negative or confused. Many of these reactions are based on misinformation. This new feature seeks to combat these misconceptions by bringing in guest writers to explain some of these species to us so we all have a better understanding and to set the record straight.

If you would like to contribute to this series as a guest writer, contact me and let me know!

Moles – Furry Tunnel Makers

by Bob Tuck

It’s one of the minor irritations of living in much of the United States and southern Canada. Whether you live in a city, the suburbs, or in rural areas, if you have a lawn or garden, chances are good that you have had dirt mounds pop up like big brown mushrooms. Some of us that are blessed with nice loose soil may have several mounds sprout across our nice, newly mowed lawn. We mutter dire threats under our breath, get some tools and a bucket, and remove the little hills of soil, knowing full well that this contest between man and (tiny) beast will resume tomorrow or the next day, when dirt mounds re-appear. Why can’t these little critters go live somewhere else besides my nice lawn?

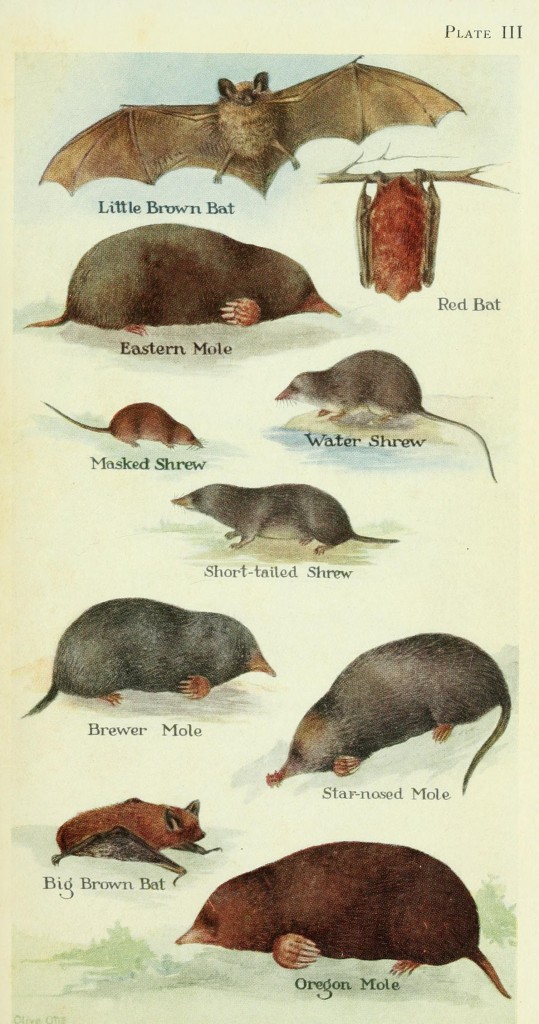

Welcome to the world of moles. These small, mouse-like creatures are common over much of the Far West, although rarely seen due to their fossorial (burrowing) life style. While many people wrongly believe that they are rodents, like mice and gophers, moles are in fact members of the Order Insectivora, along with their cousins, the shrews. But while tiny shrews scurry frantically through the leaf litter looking for their food, moles plod along underneath the soil surface, constructing tunnels and chambers where they spend the greater part of their lives.

There are seven species of moles in North America, and over 30 additional species spread across Europe and Asia. Four species are found west of the Rocky Mountains, while three species are broadly distributed across much of the Central and Eastern United States and most of south-eastern Canada. Moles are not found in the Rocky Mountains or across the Great Basin.

If you live west of the Cascade and Sierra Nevada Mountains from Vancouver, B.C. to northern Baja, you have probably seen the tell-tale signs of one of the four mole species that inhabit this area: mounds of bare soil, or long thin ridges created when a mole tunnels through the soil near the surface. Besides lawns and gardens, moles are common in pastures, hayfields, parks, and highway rights-of way.

The Pacific Northwest is home to both the largest mole species found in North America and the smallest, and perhaps most unique. The Townsend mole can exceed 9 inches in length, including a 2-inch tail. The Townsend is the common mole of the lowlands of Puget Sound and the Willamette Valley.

The smallest species of mole in North America is the shrew mole, which measures only 5 inches in length. As its name would imply, the shrew mole has many characteristics of a shrew. It is the least subterranean of the moles, and often forages through the leaf litter like shrews. It has even been known to climb into low bushes looking for prey. Unlike other moles species, shrew moles are known to have multiple litters. It is found in wet, forested, areas, often along streams or wetlands, from Vancouver, B.C. to south of San Francisco.

Moles possess a number of interesting adaptions that allow them to tunnel through the soil and spend almost their entire lives below ground. Unlike most mammals, their forelimbs actually stick out from the sides of the body so that the animal almost “swims” through the soil, propelled by powerful arm and chest muscles. These muscles attach to prominent processes and ridges on the bones of the arms, forearms, and feet. The forefeet are broad with strong claws, and function like miniature shovels. They even have an extra “thumb” to provide more digging capability.

The fur is short and velvety soft, black or grey, mixed with brown, sometimes with a metallic luster. The fur lies equally flat in either direction, which means that the fur does not impede the movement of the animal whether it is going forward or backward in the tunnel. Soil particles do not adhere to the individual hairs, which is also important for an animal that lives in direct contact with the soil.

As one would expect of an animal that lives in subterranean darkness, the eyes are extremely small, sometimes covered with skin, and hidden in the fur. These adaptations are, of course, to keep soil particles from getting into the eyes and causing physical discomfort or worse. They can detect changes in light, but probably have little visual acuity.

Moles have no external ears, and the openings are small and covered with fur to prevent soil particles from entering these sensitive organs. The nostrils open horizontally, to minimize soil particles getting into the air passage.

Moles depend on their sense of touch to a great degree. The muzzle is covered with tiny bumps, or papilla. These surface irregularities are actually extremely sensitive tactile organs known as Eimer’s organ, named after the German zoologist (Theodor Eimer) who discovered them in 1871. Sensory whiskers are also located on the muzzle and tail.

The star-nosed mole of the Eastern United States has 22 fleshy tentacles arranged in a star-shaped pattern around its nose, which are rich in Eimer organs. The star-nosed has the ability to locate, identify, and ingest a food object in less than .3 seconds. This foraging technique allows it to utilize smaller prey items than other moles.

One might think that an animal that lives in narrow tunnels might have a problem with reduced oxygen and elevated carbon dioxide levels; the same dangers that human miners face. Well, it turns out that the air in mole tunnels often does have reduced oxygen and increased carbon dioxide levels. Oxygen accounts for about 20% of the volume of the atmosphere, while carbon dioxide makes up a very small portion, approximately .04%. In mole tunnels, oxygen levels often reach 14.3% (hypoxic), although they have been measured as low as 6%. Carbon dioxide levels can be extremely high, reaching 5.5% (hypercapnia). So how do moles cope with oxygen and carbon dioxide levels that would cause OSHA to shut down a human mine?

First, moles have larger lungs in proportion to body size, compared to other mammals. Lungs can comprise up to 20% of their body weight. But the real secret lies in the blood itself, which has a large red-blood cell volume and densely packed hemoglobin within the cells, resulting in significantly increased oxygen carrying capacity. Oxygen also concentrates in skeletal muscles that are utilized in digging, as well as in the heart. So moles continue to go about their activities under conditions that would be difficult, if not fatal, for humans.

Moles excavate several different types of underground structures. Surface tunnels are located just beneath the surface, 1”-4” inches in depth. Surface tunnels are the primary foraging areas for moles, and produce the characteristic ridges that wander across our lawns. Moles may visit these shallow tunnels more than once in their quest for food. Moles may also make use of these tunnels in late winter and early spring as they search for mates.

Deep tunnels are commonly 4”-12” beneath the surface, but may be as deep as 3.5 feet. These deep passageways are permanent, and provide routes of travel as the animal visits surface tunnels for foraging, or returns to its nest, which is a separate chamber located off to the side of a deep passageway.

Hills of bare soil, the most characteristic indication that moles are active in a particular area, are produced when a mole pushes up the excess soil that must be moved out of a tunnel during the digging operation. Molehills can be as much as 24 inches across and 8 inches high. Moles are energetic diggers; under favorable conditions they can tunnel at the rate of 15 feet per hour. Shallow tunnels can be built at the rate of 12 inches per minute in soft soil.

Of course, all this hard work generates a huge, and continuous, appetite. Similar to shrews, moles have a high metabolism rate and must consume an amount of food approaching their body weight every 24 hours. Moles are mostly carnivorous, and while their favorite prey is the earth worm, they consume a wide variety of invertebrates, and, on occasion, a few vertebrates such as salamanders. Besides earth worms, other invertebrates eaten include insect larva, snails, and slugs. Damage to flower bulbs sometimes blamed on moles is probably caused by other animals that use their tunnels, such as voles, gophers, and mice.

The surface tunnels that moles construct are in fact foraging areas. Besides capturing and eating prey items as they are located during digging, moles may re-visit these tunnels and consume worms or other prey that have fallen into the tunnels, which are, in effect, food traps.

Moles do not store large amounts of body fat to tide them over periods of scarcity, but they do store food, mostly earth worms, in special chambers constructed for this purpose. Mole larders have been examined that contained several hundred earth worms that are immobilized, but not killed, by a bite to the head.

Except for the mating season in late winter and early spring, most moles occupy solitary home ranges. During the breeding season, males use the tunnel network to locate females, although they will also occasionally travel on the surface during this time period. The females produce litters of 2-7 young in a special nest chamber that is lined with grass and other soft material. At about 6-7 weeks, the young disperse a short distance and establish their own territories.

Due to their subterranean existence, moles are not subject to high predation pressure. Most predation occurs during the mating season and during dispersal of young. Hawks, owls, coyotes, badgers, and snakes are known to occasionally prey on moles.

The major threat to most moles is flooding that occurs in their lowland habitat during the fall and winter. At those times the tunnels may fill with water and the moles will drown if they cannot exit the tunnel system quickly.

While moles may be a nuisance on occasion, they perform many ecologically important functions. They consume large quantities of harmful insects that are injurious to garden plants. In addition, their tunneling and mound-building mixes the soil, bringing mineral-rich material to the surface. Also, their tunnels help aerate the soil, as well as carry water, all of which contribute to the healthy growth of plants.

If you feel you must remove some moles, check with the local office of your state fish and wildlife agency. Certain control methods may be illegal in some states. For example, traditional mole traps that grip the body are not legal in Washington State.

So, the next time you say nasty words about the little animal that produced those annoying brown mushrooms in your lawn, take a moment to think about what a wonderfully adapted animals moles are. The short time it takes to remove the little piles of soil is a small price to pay for the contribution that moles make to the health of our environment.

About Bob Tuck:: Bob grew up on a farm in the Yakima Valley of Washington and has been a fish and wildlife biologist since 1977. He is the principal at Eco-Northwest and has also done environmental education.

Very interesting! I know we have at least one underneath our bird feeder area. Do they occasionally eat seeds?

Yes, the Eastern mole is known to eat seeds, as well as the insects that the seeds attract. BT

What an amazing animal…fascinating post too! This is one animal we do not have yet where I live in central NY…my cursed critter is the vole as they do real damage to my gardens… I am not so worried about my lawn as I am eliminating more of it.

Thank you. According to several references I checked, there are two species of moles in your part of New York-the hairy-tailed mole and the star-nosed. Might check with your neighbors and see if they have seen evidence of moles. Voles can be a problem; out here they sometimes girdle young fruit trees in the winter. BT

Fascinating post, thank you. I used to laugh at my dog who would start digging up the yard for no apparent reason until I read that dogs can hear the moles squeaking in their burrows,

Fabulous article and I love the vintage illustrations that go along with the information. I have never seen a mole but we have marsupial moles in Australia I believe.