Located on the divide between the Finnish Lakeland and the Lapland lies Syöte National Park. The name ‘Syöte’ comes from the ancient Sami language, meaning ‘blessed’, and the indigenous Sami people have used the land for thousands of years. Traces of ancient Sami use can still be found in the park, but there are many other traces of land use from more recent times.

In the 1500’s, people began settling in the area, bringing their slash-and-burn tradition with them. They began clearing the land of trees to use as agriculture, often times accidentally setting forests on fire. Until the 1800’s, much of the land was cleared of the forest and the practice was not stopped until the formation of Metsähallitus, the government entity responsible for state owned lands. The clearing of the land wasn’t stopped for ecological reasons however, it was ended for the benefit of logging and sawmills.

The forest wasn’t the only habitat destroyed when settlers arrived, the ancient mires were also impacted. As the forests regrew, crofters turned their attention to raising cows but had to find a way to grow the hay required to feed the cattle during the winter months. To grow the hay they built dams in the mires to flood the landscape and supply the hay with water in the growing season. In addition to cattle, the new inhabitants also took the techniques of the Sami and began herding reindeer. As I found when we drove through the area, reindeer are still abundant in the park and we saw them everywhere we went. Until the 1900’s the area was heavily used by crofters as well as loggers who harvested the forests for the growing sawmill industry on the coast.

Syöte National Park as it is now was established in 2000 and encompasses 299 square kilometers (115 square miles), of diverse habitats from fell to mire and ravine. I spent a few days exploring the different trails in July this year in the rain and the sun.

NAAVAPARTA

The heart of Syöte National Park is the Visitor’s Center and many of the trails begin there. Inside the Visitor’s Center is a display about the history of the land use of the park and maps of the park, including very hand individual brochures with maps for each trail. The Naavaparta Trail is one that begins at the center and on the first overcast day, I walked the 3 km circle trail. The level landscape the trail traverses through was mostly Scots Pine with a thick understory of bilberry, which were not yet producing the blue berries that are so abundant throughout Finland. Many ant hills rose up through the bilberry plants like small mountains in the forest, some upwards of four feet high. The bilberry often continued growing up the ant hills as though they were just another part of the land.

Usnea lichens hung from the branches of the pines while moss covered fallen trees with mushrooms sprouting from the sides. I spotted a few slime molds on the down wood, one was a still growing mass, probably of Fuligo septica. There were also some bright pink Lycogala sp, and another immature mass. The understory was not a single species, but a mix of bilberry and tall, star-shaped mosses with a scattering of white and purple orchids.

VATTUKURU RAVINE

Later in the day I walked the Vattukuru Ravine Nature Trail, a 2 km loop that led down into a ravine that is the popular haunt of Siberian flying squirrels. I didn’t see any squirrels, or much other wildlife because of the rain that had arrived and stayed for the duration of the walk.

This landscape was not at all flat like on the previous walk, instead I stepped down between large lichen and moss covered boulders and over long ridges of rounded rock. Bilberry still covered most of the understory, but other plants like heath, Dwarf Cornel (Cornus suecica) and Cloudberry (Rubus chamaemorus) found room to grow. Growing among wet expanses of moss, ferns sprouted up as though miniature trees and in a few open meadows, purple orchids sprouted.

At the bottom of the ravine a lean-to-shelter sat alongside a small, moss lined creek. On slopes rising high on either side, boulders sat covered in thick mosses and lichens. I followed duckboards through a wet meadow which led to a staircase that was in the midst of being replaced, balancing on the exposed beams to take me up a fen and out of the ravine.

Despite the rain, or perhaps because of it, the ravine was a green and lush oasis and one of my favorite places in the park.

PYHITYS

The landscape of Pyhitys may have been my favorite place in all of Syöte National Park. The 2 km trail led uphill, gradually at first and then more steeply and I had to keep my eyes down to step over roots and rocks. Near the top, a small, ephemeral stream ran down the path, creating miniature waterfalls and small pools of water among the rocks and roots. The top of the trail didn’t come suddenly, but gradually as large boulders showed up one by one along the sides of the path. Between the boulders, narrow canyons beckoned me to explore the lichen covered rocks and see what lay beyond.

The summit of Pyhitys is the highest point in the park and large stone rocks, or ‘tables’ dominate the space creating a wide open area to view the surrounding landscape. But I had to wait for that view because it was coated in a thick layer of fog when I arrived at the top of the fell.

These stone tables are far more than a scenic point though, they were used from ancient time by the indigenous Sami people. Every year they left offerings, goods from the lakes and forest, to safeguard future harvests.

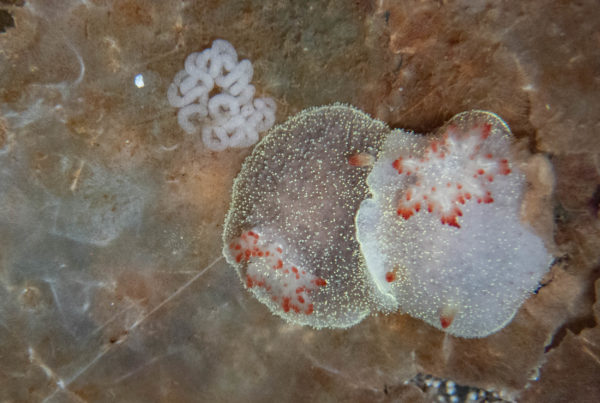

Between the stones, crowberry and moss grew in small valleys, while in cracks and crevasses on the large rocks, miniature gardens of moss and lichen flourished. It was the lichens that had me absolutely mesmerized. Not only were all the rock faces covered in them, there was an astonishing diversity. Flat, crustose lichens of white dotted with red stood out while brown lichens grew like flowers from the stone and bright yellow lichens with black spots gleamed like flowers. The closer I looked, the more I saw. Cladonia, or pixie cups grew along the sides of the stones and lichens that looked like coral grew nestled alongside the moss. In other places, different lichens grew together creating a map, each species a different country on the planet that was a boulder.

Eventually the fog burned away and I could see a large lake in the forest of Scots Pine and smaller lakes barely visible amongst the expanse of forest below the fen.

SOIPEROINEN

An hour’s drive to the northeast of the visitor’s center, I walked along an esker between two lakes, Soiperoinen and Rääpysjärvi. Eskers are long, narrow ridges, the remnants of the glacial age, deposits of sediment left behind by melting ice. The tree covered ridge led right between the lakes where I spotted a flock of Arctic Loons floating on the water. Up in the trees, Great and Blue Tits foraged, busy feeding their noisy fledglings. Although I didn’t see them, ancient hunting pits used by the forest Sami were hidden on the hillsides.

At the far end of the 3 km loop I walked across a small bridge over the end of Soiperoinen where I could see fish swimming in the clear water below. Caddisfly larvae walked under water along the lake’s edge. Further on, in the forest a bird caught my eye with a flash of red and I waited until it came close enough to view as it flitted from tree to tree, pausing briefly in the sun before launching off again. It was a Common Redstart. Not long after, I watched a pair of Eurasian Three-toed Woodpeckers foraging up a tree.

Back at the beginning of the loop where a day hut sat, I hunted the water’s edge for invertebrates. Dozens of water striders skimmed along the surface of the lake and when I looked closely, I found many of them were covered in bright, red mites. When I looked up, the lake’s surface was covered in small, radiating circles as something unseen continuously touched it. It took a while to discover they were caddisflies swarming over the lake, creating ripples as they touched the water’s surface.

The caddisflies landed in the grasses lining the lake’s shore as well. And always present in the park, deer flies with bright green eyes landed on me and followed me around. A jewelwing damselfly tormented me by vanishing each time I noticed it, but I was lucky to see an iridescent green Brilliant Emerald dragonfly land. Read my Dragons of Finland entry for more.

KELLARILAMPI

The final trail I walked was not a lengthy one, and half of it was temporarily missing. The very short 1 km circle encompassed many of the habitats of the park. It started out through a Scots Pine forest briefly, before opening up and passing through a small mire and alongside a bog pond. Dragonflies flew around the pond and the edge had many interesting plants. I got down low and discovered two different types of carnivorous sundew plants. English Sundew (Drosera anglica) grew tall, slender leaves covered in the tiny, sticky dew while Round Leaf Sundew (Drosera rotundifolia) grew low to the ground with round, flat leaves, also covered in the deathly sticky drops.

Along the trail to the lake I found small blue butterflies, a Painted Lady butterfly and more horseflies. The duckboards along the lake’s edge that were the return route had been removed, so I returned back the same way I came, without complaint, past the dragonfly pond once more.

CONSTRUCTED WATER

Later in the day our group went to a lake near our cabin to swim. While everyone was playing in the water I walked along the lake’s edge and found a small creek running away from the lake. I followed it and found flowers along the creek’s edge which were absolutely covered in insects. There were large round, yellow and black beetles, big, slender yellowish green beetles, small tortoiseshell butterflies, sawflies, bees, wasps and more flies than I could believe. Dragonflies and jewelwing damselflies flew along the creek and up on the bank I found dozens of sundew plants. I spent a couple of hours along the short stretch of the creek taking hundreds of photos of the various insects along the water’s edge. It was astonishing how many there were.

Consulting a map later to learn the name of the lake, I was surprised to find there was no water on the map. It was a newly constructed lake and creek, an artificial landscape that had already become a very busy summer stop for the area’s invertebrates.