Over the last few weeks I’ve had the chance to visit a few docks and go dockfouling to see what marine life is living on the sides of floating docks. The first dock I visited was in Bremerton and while I found only a couple nudibranchs, there were probably thousands of jellyfish. The largest and easiest to spot were the handful of fried egg jellies (Phacellophora camtschatica) but looking closer revealed masses swarming between the docks. Smaller, but still easy to spot were the dozens of water jellies (Aequorea sp.) with white lines radiating out from the center of the bell.

It wasn’t until I laid down and started to watch that the thousands of other jellies became apparent. I spotted a lot of cross jellies (Mitrocoma celluaria) and a couple of comb jellies (likely Pleurobrachia sp.) caught my eye. As I looked ever closer, I noticed a jelly that was much more bizarre. Not only was its appearance strange, it had a long, thick blue tentacle in the center, but its movement was also different as it darted around, very unlike all the other jellies in the harbor. After a bit of research back home, I figured out these were Sarsia tubulosa jellies. I also saw a jelly with a red center, but wasn’t able to identify that one yet.

The truly astounding moment came when I was laying down trying to photograph the jellies and realized that the usual sediment in the water was mixed with thousands of teeny jellies. They were no more than half a millimeter in diameter. Some were clear, but many were greenish. It was impossible to photograph them because they were so small and transparent, but I happened to capture them in the photos with other jellies. But no matter how hard I tried, I couldn’t capture the sheer abundance of the tiny jellies that day.

Another thing I was astonished by was the sheer amount of skeleton shrimp. While they can be very abundant at times, that particular day, some patches of seaweed and hydroids were absolutely swimming with skeleton shrimp. Not only were they incredibly abundant, but their behavior was different. They were decidedly more aggressive and I suspect it must have been peak mating time for them. I spotted a few with odd bumps on them that looking at closely, looked like they may have been eggs.

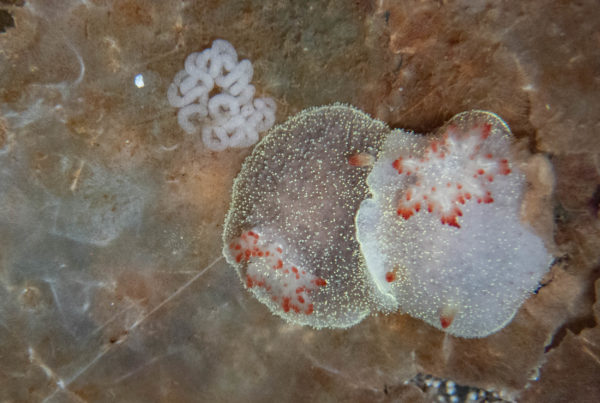

Later I visited docks in Tacoma and found a handful of nudibranchs, but no jellies save a couple fried eggs. I saw the usual Thick-horned Nudibranchs (Hermissenda crassicornis), a Red-fingered Coryphella (Coryphella verrucosa) and one of the tiniest White-line Dirona (Dirona albolineata) I’ve ever seen. But I also found another tiny nudibranch, one that’s always tiny and always adorable, the Green Balloon Aeolid (Eubranchus olivaceus). They’re pretty reliably found on certain hydroids, making them one of the easier nudis to find, despite their tiny size.