Low tides have come and gone while I sat at home looking at the tide charts, wondering what I was missing during the pandemic. But with the easing of restrictions here in Washington, I finally ventured out to my regular haunt in West Seattle for the first two times this season. My first outing was not very exciting, I found only a single nudibranch and not a whole lot else. This week however, I had more success in not only finding a few nudibranchs, but also making some discoveries new to me.

Summer has officially begun in Seattle, and this week offered sunny weather and remarkably calm water for searching the tidal zone. It wasn’t long before I found the first nudibranchs, but at first I didn’t see them because the rock I had picked up was full of interesting life. There were two different kinds of scale worms, which are marine worms with overlapping scales and many have bristles lining the sides of their bodies which look like legs similar to centipedes. Many scale worms are commensal and live on other marine invertebrates, consuming detritus. Among the wide variety of other animals scale worms can be found on include sea stars, limpets, chitons, sea cucumbers and even nudibranchs. Many scale worms live independently, or are more opportunistic, switching to living on another animal or back again.

Also on the rock was one of my favorite worms, a flat worm. These are very easily overlooked because they are so very flat and often blend into the rock. When they move, their bodies seem to take on whatever shape they slide over whether it’s a barnacle or bump in the rock. Flat worms have two tiny black spots on their heads, often set inside a light colored circle, making them look like they have cartoonish eyes. But these eyes are rudimentary, detecting light, but not seeing much else.

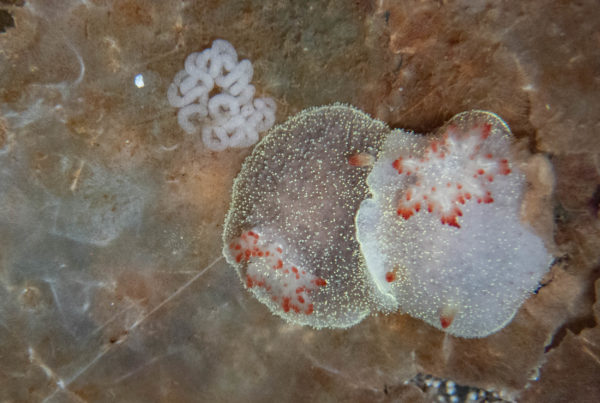

Next to the worms were three brown lumps, Barnacle-eating Dorids (Onchidoris bilamellata), a very small species of nudibranch that, as the name implies, feed on barnacles. Where there are acorn barnacles, as there were on this rock, I frequently find these unassuming carnivores. But these had been doing more than feeding on barnacles, next to them was a small, white mass that upon closer inspection revealed was actually composed of tiny, white dots in a gelatinous ribbon. These were the eggs of the nudibranchs.

It wasn’t long before I found the first of several Horned Opalescent Nudibranchs (Hermissenda crassicornis). These are usually the nudibranch I most commonly find in Seattle. Aside from these and the Barnacle-eating Dorids, I didn’t find any other nudibranchs during my explorations and I was surprised because I frequently encounter sea lemons, leopard dorids and the shaggy mouse nudibranch, among others. However I did see the eggs of sea lemons, so they were there somewhere.

This particular beach is usually full of Orange Sea Cucumbers and they are very easy to find, even under rocks, because of their bright color. However this visit I spotted something new, a white sea cucumber. It was next to the usual orange version and looked remarkably similar with the exception of being white. After a bit of research, I believe it may have been a White Sea Cucumber (Eupentacta quinquesemita), a species similar to the Orange Sea Cucumber. There is another white species called the Pallid or Pale Sea Cucumber (Cucumaria pallida), but that species has 10 tentacles and from the photos I took, it looks to me like the one I saw has only 8. The White Sea Cucumber also has orange colored tube feet (the Pallid is all white) and after I read about this, I realized I had seen the body of a sea cucumber that day which I thought was a very light colored Orange Sea Cucumber, but was probably in fact, a White Sea Cucumber. Of course I failed to take a photo of it.

But that wasn’t the last of my discoveries of the day.

Tunicates, also known as sea squirts, are often overlooked because they are sedentary and often strange in shape. But the two I found were hard to overlook because of their bright colors. The first was something that looked like a bright orange version of a sweetgum seed. It was a spiny, oblong shape perched on a narrow stalk attached to the rock. I later found a couple more out of the water and when I poked at them, discovered they squirted out water. And now we know why they are called sea squirts!

From looking at my books, I believe this one was a Stalked Hairy Sea Squirt (Boltenia villosa). I didn’t notice the siphons until I looked at my photos later, but you can see one siphon open in the photo above, near the center of the tunicate. They take water in through the siphon to collect food before squirting it out again. It was a really good sea squirt day because I found another new one too!

The aptly named Shiny Red Sea Squirt (Cnemidocarpa finmarkiensis) was also easy to see due to its bright color, even underwater. But unlike the previous tunicate, this one was perfectly smooth, although looking closely showed it does have a slight texture. The two siphons are easy to see on this species and make a + shape which you can just see in the top siphon in the photo above. This species is found along the Pacific west coast, but also up into the arctic and further west to Asia. In fact, in Japan, it’s been found in depths to 540 meters and is usually found in the lowest intertidal zones.

It pays to always examine and poke things during low tide because you never know what to expect! Even though I’ve been going to this exact spot for a few years now, I still notice things I’ve never seen before and can’t even classify immediately.