With a sunny but cold forecast for this weekend I wanted to get out before we returned to rain next week. I had been exploring quite a bit of the eastern side of the Olympic Peninsula near the end of my 365 Nature Project going to Dungeness National Wildlife Refuge, Ediz Hook Reserve for the Birds, Fort Flagler and Vashon Island and I wanted to keep visiting the area. I had seen Point No Point mentioned a few times in various books and decided to visit there yesterday. Point No Point is on the next small peninsula south from Fort Flagler, located directly west of the southern edge of Whidbey Island. The landscape reminded me very much of Point Robinson on Vashon Island with a lighthouse and a curved, sandy beach lined with driftwood. The main nature draw of Point No Point is that the waters off its beach are where multiple currents meet and during a rip current the water churns up fish drawing in birds.

My timing was lucky and when I arrived I could see that was exactly what was happening. The water directly off the beach was smooth and calm, but a short distance out the water churned in a rough wake as though a large ship had just passed by. I could see dozens of gulls in these waters riding the current of the outgoing tide before flying up in the air, returning to the south end of the rough water and riding it down again. Farther to the north, hundreds of gulls gathered in these rolling waters.

The gently lapping waves on the beach soon gave way to large and noisy waves breaking against the smooth sand. This lasted only a few minutes before returning to calm again, but the birds persisted out in the water. There were mostly gulls, but I spotted a few grebes as well and quite a few harbor seals. I walked along the beach before exploring the wetlands adjacent to the beach where a dozen Great Blue Herons stood on the frozen ponds. I heard Red-winged Blackbirds calling and spotted a small group of American Wigeons on the edge of one of the frozen ponds. As I reached the end of the wetland trail, a pair of Bald Eagles chittered, flying in and out of the Douglas Fir trees.

I walked back along the beach studying the different textures and shapes of the driftwood and looking at the shells the waves had left behind. The shady sides of the driftwood were white from frost, not something I’ve often seen on our beaches. Some of the dry sand was likewise frosty in the shade. I wandered back and forth between the driftwood and the edge of the water where I followed the crow’s tracks left behind in the wet sand. No other birds were searching the sandy shore along this part of the beach that I saw. I could see a great many gulls further to the north and looking at my map I saw another park called Norwegian Point County Park and decided to stop there to see if I could get better looks at the birds in the water.

I crossed the narrow grass when I arrived and stepped down onto the beach and could see the gulls in the water. However, they were in the water just to the northwest, around the corner where the private shoreline began. I did notice a couple of Sanderlings foraging with a Killdeer along the shore and a male Red-breasted Merganser fishing along the shore. Further out in the water were mostly gulls, a couple of loons and Pigeon Guillemots in their winter colors. I watched the gulls for a time as they would fly south along the shoreline, dropping into the water in a group before moving back north along the beach. I marveled at the tracks the receding water had left in the sand. Like reverse watersheds, the largest, deepest track was on the uphill side of the beach and as it went down the slope the track branched and braided into a dozen or more smaller channels. It created beautifully intricate, yet temporal patterns in the sand.

My final stop of the day was Foulweather Bluff, a Nature Conservancy preserve, located on the west side of the peninsula. After a short walk through a coastal forest I arrived at the beach and could see a wonderful tidal marsh adjacent to the forest and shore. Like most other small water bodies right now, the channels were frozen over, but I’d love to revisit in the summer and see what wildlife makes use of this valuable habitat. The bluff along the beach starts low where the path comes out, but grows to a towering height quickly. The beige bluff is topped with a long row of Pacific Madrone trees, some leaning precariously over the edge. I turned my attention to the beach and was surprised to find a wonderfully rocky shoreline with plenty of wildlife to be found. The tides have been high, very high, and even though I was there at low tide, it was still nearly a plus six tide. I was delighted at this opportunity to search for shore life when most other places I frequent have been too high to find anything and I haven’t bothered looking.

Every rock was covered in barnacles and I found the usual Shore Crabs under nearly every rock I flipped. Perhaps I’ve never noticed them before, but I found several flat worms under rocks as well. To the untrained eye they would look like nothing more than a small, gelatinous mass and it’s probably only because I’ve been watching freshwater flatworms in my wetland aquariums that I even recognized a flatworm. These marine versions were fascinating to watch because they changed their form so easily. One moment they were a pile of goo, the next they transformed into a long, slender arrow. I watched one meld into the cracks in the rocks as though it were made of jello and another search with its head, lifting the flat surface up into the air. They easily change shape from a long to round and their eye spots, which are more light sensors than eyes, look like cartoon eyes, white spots with black dots in the center, looking slightly cross-eyed.

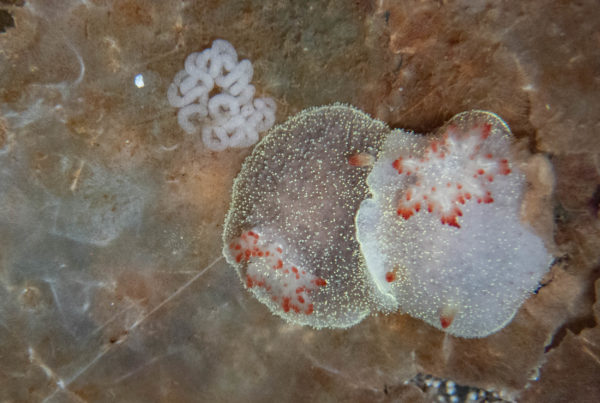

Many of the rocks were covered with tiny snails and I found a hermit crab had taken one of the shells over. I also spotted many anemones in the water and more in the sand, exposed to the air as the tide was out. A splash of florescent green tucked in between barnacles caught my attention, but I’m not sure what it was. Perhaps eggs or something some type of seaweed or algae. I heard the call of a Belted Kingfisher and looked up to see a pair flying along the shoreline in front of me making their way to a small bay. As I watched, I saw them hovering over the bay and landing in the madrone trees on the bluff. A few wigeon were in the water, but otherwise there were few birds near the shore. As I wandered the beach I heard another bird call and when I looked up I was delighted to see a quartet of Black Turnstones working the shore. I followed them trying to take some photos but they kept a wary eye on me. I then changed tactics to walk nonchalantly by them, not looking at them to get the sun on the other side, and they seemed to ignore me then. I was able to find a rock to sit on and watch them forage in the sun. As though to spite their name, they turned no stones over but instead hammered at the barnacles on the rocks. Whether they were eating the barnacles or something hiding in the barnacles I couldn’t say, but I found the behavior interesting. The hammering reminded me very much of woodpeckers knocking on wood and I wondered if the turnstones have a similarly adapted brain and skull like the woodpeckers because they were hitting the rocks with considerable force.

Foulweather Bluff is certainly a place I will revisit in the future, especially in different seasons. I could happily spend all day there.