The water may get colder, but that doesn’t stop me from going dockfouling to search for nudibranchs. I’m learning as I’ve looked for nudibranchs over the last few years that many species are seasonal. We associate seasonality with birds migrating in the fall, dragonflies buzzing around ponds in the summer and even slime molds in the spring, but marine life is also impacted by the seasons, although in a less obvious manner. Each time I look for nudibranchs on the beach or on the docks, the populations change. Sometimes it’s subtle, a couple species I hadn’t seen the previous month. But other times it can be dramatic, like the explosion of Rainbow Dendronotus nudibranchs I saw when looking for a sapsucker slug. The seasonal shift means I never know what to expect and there may be few species or many, or a few individuals or hundreds. The point is, it’s never dull!

I visited some of my more regular docks back in October in search of nudibranchs and found some familiar species, but also new ones as well. There was the always present Thick-horned Nudibranch (Hermissenda crassicornis), one of the most common of our Puget Sound species (although not even they are always around as I found in December when I didn’t find a single individual during the night tides). I also saw a few Red-fingered Coryphella (Coryphella verrucosa) and White-line Dirona (Dirona albolineata), both of which had been pretty common throughout the summer months as well. In addition there was Golden Dirona (Dirona pellucida), White and Orange Tipped Nudibranch (Antiopella fusca), Green Balloon Aeolid (Eubranchus olivaceus), Shaggy Mouse (Aeolidia papillosa) and Rainbow Dendronotus (Dendronotus iris).

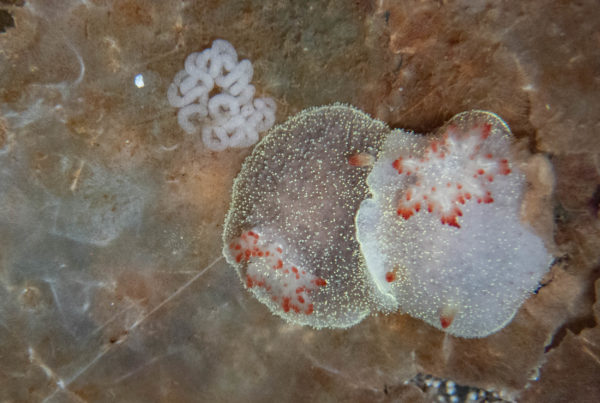

But then there were new species I hadn’t seen in Puget Sound yet. The first was Janna’s Dorid (Knoutsodonta jannae), a tiny, round nudibranch of all white which I had seen one of at Pillar Point. The other nudibranch was entirely new to me, a White-crusted Aeolid (Trinchesia albocrusta), a small translucent nudibranch with, as the name implies, white markings splattered on it. Another nudibranch I hadn’t seen before, but had seen a very similar species, was the Pacific Corambe (Corambe pacifica), an incredibly cryptic sea slug that looks exactly like the bryozoan it feeds on. The similar species I had seen is the aptly names Cryptic Nudibranch (Corambe steinbergae), almost exactly the same except without a notch on the posterior dorsum.

As always, it wasn’t only the nudibranchs that caught my eye. I was delighted to see a group of solitary hydroids. While most hydroids are colonial, a few live on their own, although they were clustered together so they didn’t strike out too far on their own. They looked like pink flowers growing on the docks, but are actually animals.

One of my favorite observations were a few fascinating flatworms. Most of the marine flatworms I encounter are hardly noticeable as they cling to the underside of rocks. But the ones I saw on the docks were doing a very reasonable nudibranch impression. They were much larger than the usual flatworms I see and although their bodies were flat, they curved them so that it looked like they actually had rhinophores. Many flatworms look very much like nudibranchs, but I hadn’t seen any like this before in Puget Sound.