There are many reasons to choose a location for a vacation like the weather, cultural institutions, food or scenery. But I confess, my main motivator most of the time are INVERTEBRATES. This summer I went to eastern Washington for a vacation in the Methow Valley, near the Columbia River. The climate is very different from here in Seattle. It’s very hot, dry and there are few trees. While that would usually be off limits for me because of my heat intolerance, I wanted to see some good bugs, so I found a cabin with AC and made the long drive.

It was worth it because I found a lot of great insects. But undoubtedly, the most memorable of my invertebrate encounters was with the ambush bugs. Outside the cabin I stayed in were a lot of yarrow flowers growing like weeds alongside the gravel driveway and I searched them constantly between bouts of cooling off in the AC. At first the ambush bugs didn’t register because they blended into the flowers and my attention was drawn by the flashy bees, butterflies and bee flies. But once I started looking more closely, it became apparent how abundant the ambush bugs were. And how deadly.

Most of the flower heads had at least one ambush bug, some had three or four. And many of them had prey. I saw a lot of small bees and moths hanging from the flowers and a close look revealed an ambush bug attached. These are true bugs, being in the Phymatinae subfamily of assassin bugs (Reduviidae family), and they’re venomous. While they’re not dangerous to humans, although they can bite if trapped against skin, they are deadly to invertebrates. They silently sit on or under flowers, waiting for their prey and then, as the name implies, they ambush the insect with their hooked forelegs and inject a venom. Along with the fluids they inject which immobilize their prey, they inject a liquifying fluid that turns the prey’s insides into a buggy milkshake that the ambush bugs drink up through their straw-like beak. And it’s a powerful venom because they can take down insects many times their own size. I saw one with a huge bumble bee that was easily four times the size of the ambush bug.

We don’t have ambush bugs as far as I know in the Puget Sound area. They’re usually found in open sunny areas on flowers like yarrow, aster or goldenrod. They’re known as jagged ambush bugs and they have a fierce appearance. Their colors vary from yellows to white and green and they look like they’re wearing wicked, spiky armor. The ambush bug’s hooked forelegs resemble that of mantids. They actually have wings, which are hard to see, but they don’t fly well.

And this is the excitement of being an invertebrate fan, there are life and death stories playing out right in front of us if we only take a moment to stop and look.

On another subject:

I recently viewed a segment of Oregon Field Guide in which you and Crow Vecchio were featured as naturalists observing, photographing, and collecting slime molds (Myxomycetes).

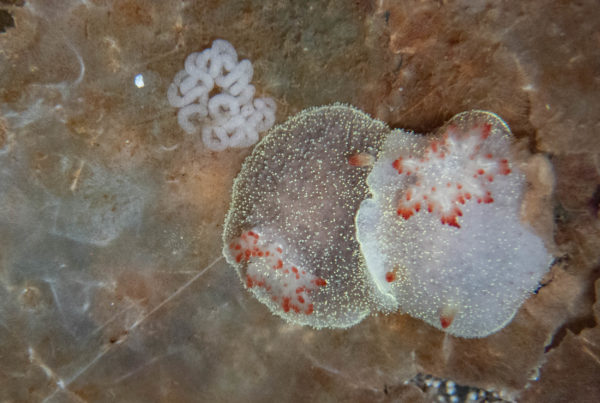

My graduate project in biology at UW from 1970-1975 involved the study and distribution of montane Myxomycetes, primarily from Washington State. I personally found their life cycle, with the distinct phases, to be quite fascinating, as well as the variety of kinds of fruiting structures found among the various species.

Coincidently, I recently sorted through my collection of fruiting bodies in preparation to donate it to a permanent herbarium collection, possibly at WSU.

If you have any interest in further conversation about Northwest slime molds, let me know.