Female Blue Orchard Bee via Crown Bees

As honeybee populations suffer from colony collapse disorder, some people are looking to our native bees to see how they can fill in. Dave Hunter from Crown Bees is one of those people. I recently took a class from him about raising mason bees and learned a great deal about why we should raise mason bees and how to do it successfully. The following information comes from that class as well as the thoroughly informative Crown Bees website.

Why Blue Orchard Bees

Groups like Crown Bees as well as individuals, are investigating the use of native pollinators to assist where the honeybees are failing. They have created the Orchard Bee Association to bring their knowledge together to “team on research, development, pollination methodologies, and health practices”.

The focal species, the Blue Orchard Bee (Osmia lignaria), has certain benefits over the honeybee such as foraging in the cold weather or light rain. They also stay close so it’s easier to target certain plants such as fruit or nuts trees. Blue Orchard Bees do not compete with the honeybee and they can even work alongside each other. In addition, the Blue Orchard Bee is not choosy about their pollen and will visit a wide range of flowers. They are messy pollen gatherers unlike the honeybee who packs wet pollen neatly onto their leg. The Blue Orchard Bee gathers the pollen, but being dry, much of it falls off and as a result, they pollinate nearly every flower they visit. One Blue Orchard Bee can pollinate 2,000 blossoms in a single day, the equivalent of what 100 honeybees can do.

About Mason Bees

There are many species of mason bees, 120 in North America alone. Mason bees do not produce honey, instead females gather pollen for their larvae. Mason bees are small and easily confused with flies, however they have longer antennae, smaller eyes and four wings. Females are larger than the males, about 3/4″ and 1/2″ in length respectively, and the females have shorter antennae. They are incredibly gentle bees and although the females can sting, they very rarely do and do not even act aggressive at their nests. A Blue Orchard Bee’s sting has very low venom and produces the equivalent of a mosquito bite.

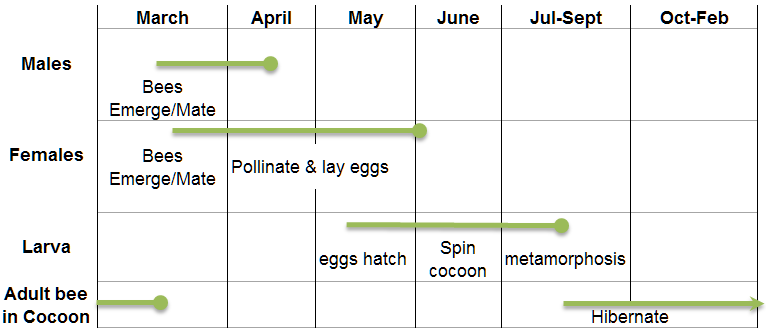

They have a very short active life, only foraging for 6-8 weeks in the spring, usually sometime during March, April or May. Males emerge first and do a little pollinating before waiting for the females to emerge. Once the males mate they die shortly thereafter. The females emerge two weeks after the males, mate and start to build their nests. They lay eggs in their nests, leaving pollen with the eggs and then use mud to seal the egg and pollen in an individual chamber. The eggs hatch into larvae and feed off of the pollen before creating cocoons which the adults will stay in as they overwinter.

Bees use three types of nests for their young; hives, which account for about 30% of bee species, the ground, also 30%, and holes, 40% of species. Mason bees are among species who use holes for their nests. During the class we opened some of the nesting straws, which are about 6″ long, and in mine there were between 9-11 bee cocoons in each one. Mason bees do not make their own holes, in a natural setting they’ll use snags or old trees. They will also make use of human structures such as shake siding and even outdoor furniture.

The Mason Bee Life-Cycle via Crown Bees

Mason Bees Essentials

Like most other pollinators, landscaping can help attract mason bees. Many of the same ideas used for landscaping for other pollinators is also true for mason bees such as avoiding all pesticides and planting plenty of flowers. Native spring flowers are perfect for the Blue Orchard Bee because they emerge in the spring and don’t have a strong pollen preference. Composite flowers with open petals are easier for the mason bees to harvest pollen from, and deep flowers, such as lilac are more difficult. Because they don’t forage too far from their nest sites, the flowers need to be within 300′ of a nest structure.

They also require a source of mud which they use to divide the chambers of their nest, and the mud needs to consist of more clay than sand. While this isn’t usually a problem in western Washington, if there is no close mud source, one can be created. This can be done by digging a shallow hole, lining it with plastic and filling with soil and keeping moist throughout the spring. See directions on making a mud hole here.

The third essential is to provide nest shelters. The basics of a mason bee nesting hole is a 5/16″ hole at 6″ deep. There are many materials for making holes, some commercially available. Paper tubes with a paper insert are perhaps the best solution, but reeds also work well. Plastic straws are not good because the dampness of the pollen in the nest compartments is trapped, and can end up killing cocoons where paper pulls the moisture out. Wood blocks are not idea either because they can be difficult to clean and inspect, although using the paper inserts in wood blocks is an option. Mason bees require a clean hole and if a block of wood is reused it can contain a build up of pests.

Female mason bee at nest straws via Crown Bees

One of the pests that can build up are pollen mites which are common on flowers, and the foraging mason bees can inadvertently pick them up. As they enter their nest hole they leave some behind. The pollen mites will eat the pollen left for the larvae and if too many build up in a hole they can deplete the pollen before the larvae emerges and they will starve to death. Another potential problem is chalkbrood, a fungal spore that can also be found in nest holes and will kill the larvae if eaten. It is easy for the adults to pick up and it can easily spread among nest holes, flowers and other adults. For more about potential pests see Crown Bees Pests page.

The paper straws or reeds need to be protected in some type of shelter that will keep them dry. Anything from manufactured structures to a plastic soda container can work for this. The shelter should be placed where it gets morning sun to help the bees warm up in the morning. It should also be placed so that the open front is out of the direct rain and wind. Also avoid putting it too near bird feeders or over water. Mason bees identify their hole with scent, but they have to get close to smell it. Stacking the straws so that some stick out further than others helps the bees to identify their own hole.

Bringing the straws in during June will help avoid predators and pests, as well as preventing other species using a partially filled straw. Blue Orchard Bees lay their eggs earlier than many other species and also emerge earlier. If another, later mason bee species were to also use the same straw, and the Blue Orchard Bees emerged first, they could either get stuck in the back and die, or kill the other species chewing their way out. A second set of straws can be set out for the later species, while the earlier ones are placed in an unheated shed or garage or a fridge.

For a great amount of more detailed information on what to do each month of the year such as harvesting, checking for problems, washing cocoons and putting them back outside, see Crown Bees Seasonal Instructions page.

Further Reading::

The Crown Bees website has a great deal of information about all of the topics discussed above and much more.

Blue Orchard Mason Bees:: BC Ministry of Agriculture and Lands

Orchard Mason Bees (PDF):: Washington State University Cooperative Extension

I”m wondering if I can raise Mason Bees in southern New Jersey>

I have two questions about mason bees.

I purchased a tube with 5 bee cocoons in it. I just took them out of my frig. One cocoon is so large in the tube that I can’t fit it into my house with the 5/16 holes. And, in the plastic bag, there are a lot of little specks – are they little poops? Do I clean them off before I put the tube outdoors.

It makes no sense to me how the cocoons at the back of the tube start to leave the tube first. How does it push out the one in front and the one in front of that, etc. Is the yellow fluggy stuff the pollen in the tube from last year?

thanks,

Good morning Kelly

I just received my first order of mason bees! I have them now in a large plastic opaque box with a small plate of sugar water in the event they need energy and hydration. Most of the mason bees that I ordered are still in their cocoons, which are in the fridge and will be taken out in about a week when they are to be transplanted outside.

I have a question that perhaps you can help me with. Just starting out in (honey) Bee Keeping, so I know there are no guarantees, but are there any ways to try to keep the mason bees attracted to their mason bee house ( I have two in the plastic box with them. I am hoping if I keep the mason bees in the box with their new mason bee house, they will get used to it) and not fly away, once they are released? They will be released in a property with flowers and fruit trees so perhaps that will keep them around. It would be a bummer if they simply fly away. Thoughts?

Best wishes,

Roy and Anna

My son has a bee tearing pieces of flower petals off his bougainvillea plant. The bee is bringing them to a hollow bamboo stake and building a nest. What family in the mason bee species uses flower petals to do this? He found an article on Osmia avosetta bees however we can’t find if they are native or living in Las Vegas Nevada. Are there others that tear flowers to do this?