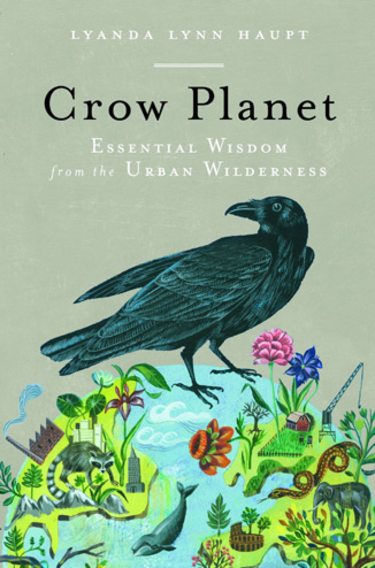

Crow Planet

Crow Planet: Essential Wisdom from the Urban Wilderness, by Lyanda Lynn Haupt is one of those books that should be read by anyone and everyone. Although the focus of the book is crows, it’s really about so much more. It illuminates for the reader of the simple and hidden urban wildlife that can be found essentially everywhere in the city, and teaches us how to appreciate and tune-in to it. Despite being an avid urban naturalist, I found it greatly opened my eyes as well. In fact, while I was somewhere in the middle of the book, I had an interesting crow encounter of my own which I recorded here. Since finishing the book, I’ve become much more in-tune with my surroundings and I’m learning to listen and observe more even during every day outings around the city. As the classic Sherlock Holmes quote goes, “You see, but you do not observe. The distinction is clear.” This is a quote I bring to the front of my mind on a regular basis, even before encountering this enlightening book. I believe naturalists and ecologists could learn a lot from Sherlock Holmes’ observation techniques. There is so much to observe.

The Corvid family, which includes ravens, crows, jays and magpies, is well known for its intelligence. For an insight into ravens, read Mind of the Raven: Investigations and Adventures with Wolf-Birds by Bernd Heinrich. Crow Planet focuses on the American Crow, a very common, medium sized bird with glossy black feathers. In addition to being highly intelligent, crows are extremely social birds, sometimes sleeping in communal roosts of hundreds of birds. They have a negative stigma, partly a cause of their interesting history and folklore. They are abundant, found in nearly every habitat, and easy to encounter in many settings, especially the city. I regularly watch them from my apartment as they forage, mob hawks, drink water from the roofs and play. There’s a building on the next block over which has a tall antennae on it which the crows use for regular games of ‘King of the Mountain’. I have also observed them in what I can only describe as playful flight, wheeling around the city, diving and spiraling before returning to normal flight.

The book does an excellent job at describing the lives of crows from their nesting behavior, to the challenges of survival, to their intelligence. This book also does an equally good job at describing the wild in the city, challenging the belief of nature out there, instead of here. Integrated into the natural history of urban crows are stories from the author about her experiences with crows. Many of the experiences may resonate with readers who experience similar encounters. For example, in the second chapter she describes a crow picking moss off curbs and when she investigated the bare spots with a hand lens, found tiny larvae among the soil and leaves. I’ve watched many times as crows pull moss off of branches of trees and I wondered what they were looking for. Perhaps other larvae hide under the moss on trees similar to those under the moss on the curbs.

One chapter discusses the author’s ‘list of naturalists qualities’, which she believes are habits practiced by the ‘best students of nature’. Some of the qualities include ‘study’, ‘name things’, ‘practice and have patience’, ‘respect the wildness of animals’, ‘cultivate an obsession’, ‘carry a notebook’ and more. The description of these ‘qualities’ make a lot of sense, it’s easy to get hung up on certain aspects of being a naturalist and this list helps the reader to become more well-rounded and focused.

The intelligence of crows is brought up many times in this book and the author discusses many studies about the subject. Many crows have been observed using tools, such as sticks to get food. Others drop nuts on streets to crack the shells while others will go further and drop the nuts in the path of cars and let them crack the shells for an easy meal. The book includes many wonderful stories of crow observations and then explains much of their behavior with references to scientific studies. One of the studies mentioned was done at the University of Washington which looked at the ability of crows to recognize specific humans. There was an excellent episode on Nature all about this study which can be watched online, called A Murder of Crows.

An amazing feature of the American Crow, their extensive language of calls, is also talked about. The book describes many of the calls that we understand, and their meaning. One of the calls the author discusses is the assembly call, which is one that I believe I hear from time to time when the crows are mobbing a raptor. It’s easy to observe because crows will start coming in from all directions. In fact, I often wonder if their assembly call is universal, because I see gulls joining in the fray when the crows put out the call.

Another interesting discussion is about the Rule of Saint Benedict. One of the stories about Saint Benedict was that of a jealous rival, which sent Benedict a poisoned loaf of bread. A crow, with whom Benedict shared his daily bread, detected the poison and took the loaf away. Benedict’s lectio rule was to choose a book and commit to reading the book thoroughly, completely, and alone. The author talks about how this can be applied to the study of nature by serious observation and contemplating a single question at a time.

The connection of crows and death is also addressed in the book along with our discomfort of them. Because of the scavenging nature of crows, they have long been disliked and often feared. Crows and ravens have also been associated with war, following soldiers and feeding on their dead. The Black Death also gave crows and ravens a bad name as they scavenged the dead left in the streets. Their scavenging eventually was fatal to them because after the London fire in 1666, as the crows fed on the burned victims, King Charles II led an effort to exterminate the birds.

This book cleverly manages to blend personal stories with the natural history of crows and the wilderness of the city in a very entertaining read. No matter whether you’re a naturalist, urbanite, suburbanite or already an urban naturalist, this book will undoubtedly introduce you to some idea you never considered before.

Crow Planet: Essential Wisdom from the Urban Wilderness

Lyanda Lynn Haupt

2009

Little, Brown and Company

This is a fascinating study. However,I am puzzled to read the comment re. the Great Fire of London in 1666 and the sight of crows feasting on the victims. Amazingly, only a small number of people died, about 8, so hardly sufficient numbers to attract any significant number of carrion birds. I would have thought that in 17th century England, battlefields were more likely places to witness large numbers of bodies and therefore crows etc. Far more likely to provoke hatred of the birds across the country and not just in London which was a small place back then. Where did you source this information?

Hi Lou, thanks for reading! The information about the Great Fire came directly from Crow Planet…”The great London fire of 1666 cemented a centuries-long hatred of crows. Ravens and crows descended with such zeal upon the charred victims that the grieving survivors appealed to King Charles II, begging him to exterminate the birds, a task he oversaw with vigor. Nests were decimated and bounties paid on the skins of crows and ravens.”

As for the death toll, there were only a few official deaths, but many more may have not been counted due to being cremated or from a low class. http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Great_Fire_of_London

Here’s a quote from the BBC history page about the fire. “Officially, only four people died, but John Evelyn referred in his diary to ‘the stench that came from some poor creatures’ bodies’ and the true toll is likely to have been much higher, rising further in the following months.”

Nice post. Crows are fascinating creatures. I love to watch them here in NYC, although there are not as many in Manhattan as I would like to see. (My experience of the Pacific Northwest from Portland to Vancouver, B.C. is that it is the heart of Crow Nation.) In NYC, I watched one crow stand on a rock in the park and, holding a nut in its beak, bang it over and over into the rock until the nut split open. Seems like a lot of work for a little meat, but then I feel the same way about lobster – too much work!

hay there is this an awesome site! Great info!

Sounds like a book worth picking up. I observe crows all the time- why not? They’re everywhere, and they are very interesting. Watching them band together and chase away eagles and hawks is amazing.